Wikipedia gives a pretty good explanation of retro-futurism if you’re not really sure what it is.

Characterized by a blend of old-fashioned “retro” styles with futuristic technology, retro-futurism explores the themes of tension between past and future, and between the alienating and empowering effects of technology. Primarily reflected in artistic creations and modified technologies that realize the imagined artifacts of its parallel reality, retro-futurism has also manifested in the worlds of fashion, architecture, literature and film.

It’s nostalgia, in a way. That “pang we feel upon realising the impossibility of returning to an idealised past”. But as Mel Campbell asks in her Crikey essay:

Lurking behind many appeals to things “retro” is an ethical dilemma: how can we cherry-pick what we like about the past without somehow excusing its failings? The notion of “retrogression” implies an overarching teleology of progress — and why would you long for a past that’s politically “worse” than the present?

This is one of the criticisms you’ll hear about steampunk, for example. Charlie Stross argues:

But there’s a dark side as well. We know about the real world of the era steampunk is riffing off. And the picture is not good. If the past is another country, you really wouldn’t want to emigrate there. Life was mostly unpleasant, brutish, and short; the legal status of women in the UK or US was lower than it is in Iran today: politics was by any modern standard horribly corrupt and dominated by authoritarian psychopaths and inbred hereditary aristocrats: it was a priest-ridden era that had barely climbed out of the age of witch-burning, and bigotry and discrimination were ever popular sports: for most of the population starvation was an ever-present threat. I could continue at length. It’s the world that bequeathed us the adjective “Dickensian”, that gave us a fully worked example of the evils of a libertarian minarchist state, and that provoked Marx to write his great consolatory fantasy epic, The Communist Manifesto. It’s the world that gave birth to the horrors of the Modern, and to the mass movements that built pyramids of skulls to mark the triumph of the will. It was a vile, oppressive, poverty-stricken and debased world and we should shed no tears for its passing (or the passing of that which came next).

Campbell again:

Perhaps I’m just being nostalgic myself, but I believe nostalgia doesn’t have to be either an indulgent fantasy or shorthand for philistinism and conservatism. Clearly, the comfort nostalgia bestows is what makes it so politically powerful — and it’s politic to consider how to draw on this power ethically, rather than in the service of our worst instincts.

Nor does looking backward preclude Julia Gillard’s obsessive impulse to “move forward”. Nostalgia can express ambivalence at the swift pace of social and economic change; it lets us weigh what’s gained against what was lost. And it seems wise to seek lessons from the past, rather than assume that all we leave behind are mistakes.

It’s also looking back at the hopes and fears our ancestors had for us. Did we measure up? Have we disappointed them?

“People think there’s too much technology, but there’s actually not enough. How come we’re still stuck in traffic, not flying around like the Jetsons?

“Every day I’ve got to figure out what’s for lunch,” she sighs. “I wish I had my little pill.”

Despite the tremendous technological leaps of the past several decades, in many ways our vision of the future remains just the same as it was 40 years ago. As we hurtle into 1999, a distinct nostalgia for the unfulfilled promise of the future — mostly the idea that we would one day be liberated from the mundane — lies at the core of much of our popular culture.

Despite iPods, genetic sequencing, the Internet and Twitter, nearly a third of Americans said they thought there would be more technological advances by the year 2010.

Or is it the past’s fault for being a bit too optimistic?

In a few days it will be 2008, well into the future. Movies promised us we’d be flying cars to our jobs at the robot factory. Instead, we have to settle for iPods, free online checking accounts and AIDS. Of course, the future wouldn’t have been such a disappointment if Hollywood hadn’t gotten our hopes so high.

We can learn about ourselves from what people predicted we would be like.

Orwell warned of a world where books were banned. Huxley warned of a world where no one wanted to read books. Orwell warned of a state of permanent war and fear. Huxley warned of a culture diverted by mindless pleasure. Orwell warned of a state where every conversation and thought was monitored and dissent was brutally punished. Huxley warned of a state where a population, preoccupied by trivia and gossip, no longer cared about truth or information. Orwell saw us frightened into submission. Huxley saw us seduced into submission. But Huxley, we are discovering, was merely the prelude to Orwell. Huxley understood the process by which we would be complicit in our own enslavement. Orwell understood the enslavement.

See a cartoonist’s interpretation here.

John W. Campbell reviews Atlas Shrugged:

This work is science fiction in the same sense George Orwell’s 1984 was. It’s about equally bleak, in many respects. But it is, I think, more important; Orwell described what tended to happen. Ayn Rand describes, with powerful accuracy, some of the forces that make disaster happen … and what the methods used by the destroyers are. The psychological tricks that permit a weak, snide, useless, incompetent to bind the strong and constructive by means of that strength. The story is apparently — at first glance — a study of sociological forces. But unlike any professional sociologists’ works, it recognizes that sociology starts at home — with the individual-individual relationship patterns.

Perhaps, whether it’s an imagined future or a re-imagined past, it’s really always about what’s happening now. William Gibson:

1984 is a powerful book precisely because Orwell didn’t have to make a lot of shit up. He had Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union under Stalin as models for what he was doing. He only had to dress it up a little bit, sort of pile it up in a certain way to say, “this is the future.” But the reason it’s powerful is that it resonates of history. It doesn’t resonate back from the future, it resonates out of modern history. And the power with which it resonates is directly contingent on the sort of point-for-point mimesis, like sort of point-for-point realism, in terms of what we know happened.

Doctorow agrees:

Science fiction author Frederik Pohl said that sci-fi writers don’t predict the automobile—they predict the traffic jam.

That’s a really interesting position for him to take, because I don’t think that science fiction writers predict the future. Science fiction has always been about the present, even when it’s dressed in futuristic trappings. We write stories that try to address the effect of technology on society and vice versa. Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein, was not predicting that in the future we would all build men out of corpses and animate them with lightning. Her point was that we might become technology’s servants rather than its masters. She wasn’t really being predictive. She was worrying about the present.

Also, it’s a lot of fun:

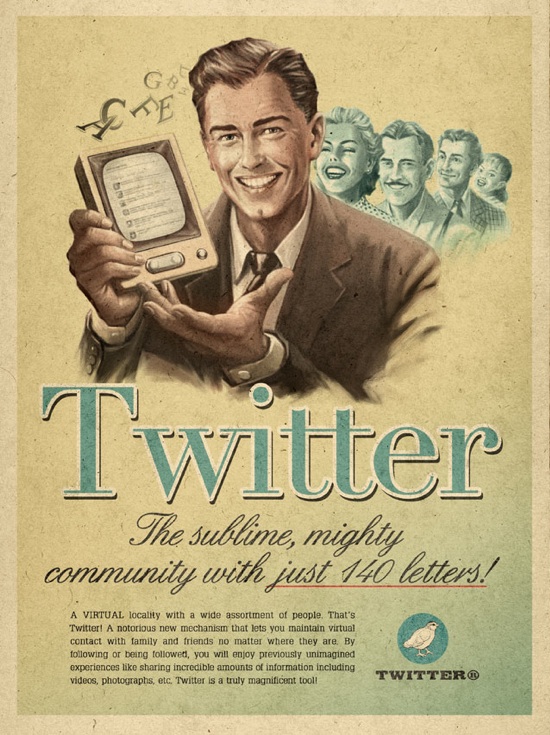

We’ll be looking at retro-futurism in the lead-up to Swancon Thirty Six | Natcon Fifty, so keep an eye on the site. You can add our feed to your Google Reader, or have posts sent to your inbox. Or watch for links on Facebook or Twitter.

2 Comments

Hey,

Those pictures are very cool. People reading this article might be interested in the current issue of UK based journal Neo-Victorian Studies, which I was both excited and disappointed to discover is a special issue called “Steampunk, Science, and (Neo)Victorian Technologies” (Disappointed because I missed out on contributing).

http://www.neovictorianstudies.com/

I read Charlie Stross’s comment on the Dickensian past of steampunk, and agree with everything he says – except the implication that a place you wouldn’t want to live is also a place you wouldn’t want to read about. No, no, a thousand times no! It’s the dreadful, dangerous, hellish times that make for the most exciting fiction. And it’s the Utopias that makes for the most boring fiction. I’ve read a couple and they are BORING! I love steampunky fiction when it creates an alternative nineteenth century that’s even more dreadful and hellish than the real one.

Isn’t that why sf futures keep on taking on backward-looking qualities? An efficient, well-organized, smoothly running world just isn’t interesting. It’s when the future gets dark and dangerous and unpredictable that we get interested, as with post-apocalyptic futures. Steampunk isn’t necessarily retro-futuristic and retro-futures aren’t necessarily steampunk (though Phillip Reeve’s Mortal Engines certainly has the best of both worlds), but it’s the same impulse in both cases, I reckon!

Richard